Table of contents

Ever wonder why your virtual machines report that their network speed is 10 Gbps, even if you haven’t got a 10 Gbps adapter in the physical box? If so, you’re certainly not alone. Knowing why depends on an understanding of the Hyper-V virtual switch.What makes this a mystery is related to the initial confusion many have as newcomers to virtual environments. There’s an expectation that hardware that shows up in the virtual machine will in some way reflect what’s on the physical host. For people accustomed to virtualization, that might seem like an absurd assumption, but it’s actually logical. A virtual machine that wants to send or receive data on the Ethernet network will need to utilize a physical adapter in some way. In fact, the exact adapter is selected when the virtual switch is created. Why then, would some representation of the physical adapter not appear in a virtual machine? The CPU shows up as is, so why not the network adapter?

Logical or not, that’s just not how it works in Hyper-V (with the lone exception of SR-IOV, which is not a topic of this article). The virtual network adapter is a complete abstraction. It is at least two levels away from the physical device.

The first level is the adapter itself. What the virtual machine “sees” as a network card is a projection into the VMBus. This was discussed in an earlier article in the Synthetic Hardware section. It’s an interface to the hypervisor’s device communication channel.

The second level is the virtual switch. This is another software construct, this time inside the hypervisor. Virtual adapters are “plugged in” to this virtual switch. So, think about the analog in a physical environment:

When you plug the server into the switch, it begins a process of auto-negotiation (unless auto-negotiation is disabled). Both sides agree on the fastest connection they both support. This is then displayed as the speed for the connection. This is what you see on the status for the connection:

The important thing to point out is that this the negotiated speed, not the actual speed of the connection. In many cases, especially wired connections in a trouble-free environment, there’s no difference.

Here, we can return to the virtual environment. There’s no physical adapter or physical switch. Both the adapter and the switch it connects to are virtual. They exist only as internal constructs of the physical computer hosting the Hyper-V environment. This hardware is typically capable of more than 10 Gbps, but this is the speed that Microsoft chose to have the connections negotiate to. This is perhaps because 10 Gbps is currently the highest speed generally available standardized hardware.

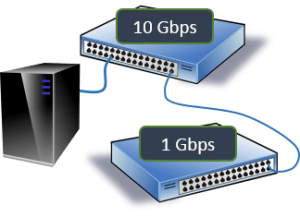

So, what about the physical connection, especially if it’s all gigabit hardware? Everything is actually working exactly as it should. It might help to think of it the way it would work if nothing was virtual. The following diagram contains a visualization:

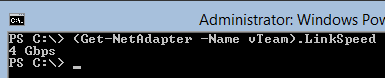

Think of how the above image translates to your Hyper-V environment. The server pictured is analogous to a Hyper-V guest. The 10 Gbps switch is the Hyper-V switch. That’s the switch that all the guests connect to. If that switch is assigned to a 1 Gbps physical adapter, then that adapter effectively represents the uplink that allows Hyper-V’s switch to communicate with a physical switch. All the guests share this single path for communication. Of course, the Hyper-V virtual switch can be bound to teamed adapters, and they would work the same way as two switches connected across multiple ports combined into a port channel. That connection speed is not reported in the guests, as they only know about the negotiated speed to their next hop, which is the Hyper-V switch. The host knows about it, though:

This is a little different from the normal negotiation process, as the teamed adapter is a software construct. The particulars are fairly trivial in nature and beyond the purpose of this article. These speeds are based on the constituent physical adapters’ speed negotiations. While also not part of this article, it should be pointed out that the team does not provide a simple aggregated pipe.

The Hyper-V virtual switch and its connected virtual adapters are essentially capable of whatever speed the host can provide, regardless of the reported negotiated speed. Their actual connection to the physical network is determined by the intermediate hardware.

If the concepts presented in this article are difficult or completely new, then you might benefit from reading our article series devoted to the workings of the Hyper-V switch.